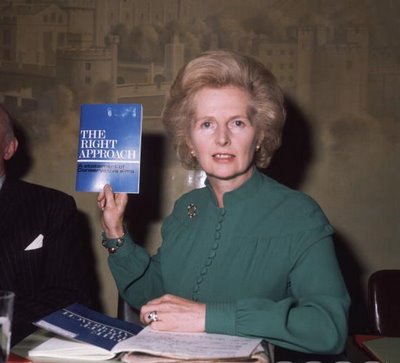

You want a lump of cole rather than a welfare payment?

“When Thatcher dies they’ll have to build a dance floor over her grave for all the people who want to dance on it.” When I was told this in a pub some years ago it wasn’t the sentiment that struck me but that fact that the unimaginative fellow speaking might have thought it was the first time anyone within earshot had heard that rib tickler.

I was born in Sheffield in 1980 and through family and support of an underachieving football club I retain ties to the place and its people. I have heard Sheffielders, some quite reasonable folk, say that they wish the Brighton bomb attack had succeeded; I have heard them joke frequently about Thatcher’s dementia.

One told me that if there was a God he would believe in him if Margaret Thatcher died. But, if there is a God, shouldn’t he believe in him anyway? And unless he was ascribing to Thatcher powers of immortality, her death is a certainty and, thus, so is his eventual embrace of theism.

You won’t find logic where none exists. The visceral hatred of Margaret Thatcher isn’t based on anything resembling rational thought. As one Sheffielder once put it to me “I dont understand all this stuff about GDPs, Taxes, RPI etc etc. All i know is that growing up in Sheffield in the 80s. Thatcher demolished a once proud city & left alot of its inhabitants pennyless, jobless & without hope. You can argue about stats all day. But that was the reality of it all. People loosing their, jobs, homes & pride.” (sic, sic, sic…)

That’s why people in places like Sheffield will be celebrating Margaret Thatcher’s death. There’s just one problem. It’s wrong.

For starters, feel the parochialism. Thatcher was bad for Sheffield ergo she was bad. Never mind the rest of the country. Never mind the GDP growth of 23 percent or the increase in the median wage of 25 percent during her time in office. For most people the Thatcher years were ones of prosperity. That’s why she regularly tops polls of most popular Prime Ministers.

This is not to say that this person’s view is worthless. But it is to say that an opinion formed simply by looking up and down your street might not be too useful.

Then, just how proud actually were places like Sheffield before Thatcher came along? How proud can any city be when it is, essentially, a vast welfare case getting by on the wealth transferred to it from other parts of the country?

That was the truth of the industrial situation in these areas. Take coal. Just before the First World War the mines employed more than 1 million men in 3,000 pits producing 300 million tonnes of coal annually.

By the time the industry was nationalised in 1947 700,000 men were producing just 200 million tonnes a year. To improve this situation, in 1950, the first Plan for Coal pumped £520 million into the industry to boost production to 240 million tonnes a year.

This target was never met. In 1956, the record year for post war coal production, 228 million tonnes were produced, too little to meet demand, and 17 million tonnes had to be imported. Oil, a cheaper energy source, was growing in importance, British Rail ditching coal powered steam for oil driven electricity, for example.

Jobs were lost in numbers that dwarfed anything under Thatcher. 264 pits closed between 1957 and 1963. 346,000 miners left the industry between 1963 and 1968. In 1967 alone there were 12,900 forced redundancies. Under Harold Wilson one pit closed every week.

1969 was the last year when coal accounted for more than half of Britain’s energy consumption. By 1970, when the Conservatives were elected, there were just 300 pits left – a fall of two thirds in 25 years.

By 1974 coal accounted for less than one third of energy consumption in Britain. Wilson’s incoming Labour government published a new Plan for Coal which predicted an increase in production from 110 million tonnes to 135 million tonnes a year by 1985. This was never achieved.

Margaret Thatcher’s government inherited a coal industry which had seen productivity collapse by 6 percent in five years. Nevertheless, it made attempts to rescue it. In 1981 a subsidy of £50 million was given to industries which switched from cheap oil to expensive British coal. So decrepit had the industry become that taxpayers were paying people to buy British coal.

The Thatcher government injected a further £200 million into the industry. Companies who had gone abroad to buy coal, such as the Central Electricity Generating Board, were banned from bringing it in and 3 million tonnes of coal piled up at Rotterdam at a cost to the British taxpayer of £30 million per year.

By now the industry was losing £1.2 million per day. Its interest payments amounted to £467 million for the year and the National Coal Board needed a grant of £875 million from the taxpayer.

The Monopolies and Mergers Commission found that 75 percent of British pits were losing money. The reason was obvious. By 1984 it cost £44 to mine a metric ton of British coal. America, Australia, and South Africa were selling it on the world market for £32 a metric ton.

Productivity increases had come in at 20 percent below the level set in the 1974 Plan for Coal.

Taxpayers were subsidising the mining industry to the tune of £1.3 billion annually. This figure doesn’t include the vast cost to taxpayer-funded industries such as steel and electricity which were obliged to buy British coal.

But when Arthur Scargill appeared before a Parliamentary committee and was asked at what level of loss it was acceptable to close a pit he answered “As far as I can see, the loss is without limits.”

Source: The BBC

Falling production, falling employment, falling sales, and increasing subsidy; that was the coal industry Margaret Thatcher inherited.

She did not swoop in and kill perfectly good industries out of spite. Industries like coal and steel were already dead by the time she was elected. Thatcher just switched off the increasingly costly life support which had kept these zombie industries going.

When Margaret Thatcher dies the streets of Sheffield will flow with ale. But the next day the revelers will wake up with headaches and Margaret Thatcher will still have crushed Arthur Scargill, will still have helped win the Cold War, and will still have shown the supposed inevitability of socialism to be the dimwitted sham it was. And those achievements will last longer than the hangovers.

This article originally appeared at The Commentator