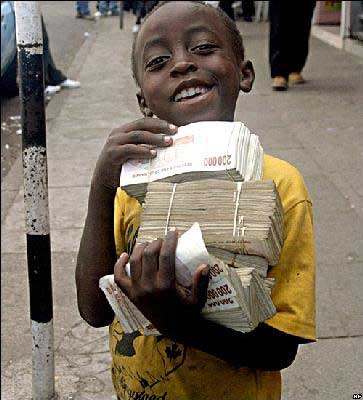

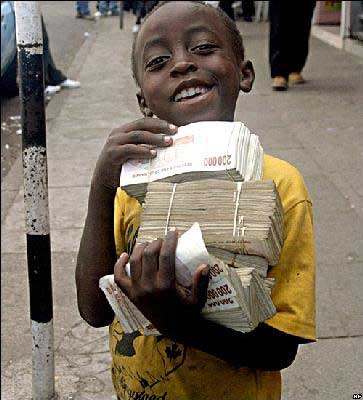

Dinner money

Dinner money

When currencies and monetary arrangements have broken down it has always been because the currency issuer can no longer fight the lure of the seigniorage to be gained by over issue of the currency. In the twentieth century this age-old impulse was allied to new theories that held that economic downturns were caused or exacerbated by a shortage of money. It followed that they could be combated by the production of money.

Based on the obvious fallacy of mistaking nominal rises in wealth for real rises in wealth, this doctrine found ready support from spendthrift politicians who were, in turn, supported by the doctrine.

Time and again over recent history we see the desire for seigniorage allied with the cry for more money to fight a downturn pushing up against the walls of the monetary architecture designed to protect the value of the currency. Time and again we see the monetary architecture crumble.

The classical gold standard

At the start of the twentieth century much of the planet and its major economic powers were on the gold standard which had evolved from the 1870s following Britain’s lead. This was based on the twin pillars of (1) convertibility between paper and gold and (2) the free export and import of gold.

With a currency convertible into gold at a fixed parity price any monetary expansion would see the value of the currency relative to gold decline which would be reflected in the market price. Thus, if there was a parity price of 1oz gold = £5 and a monetary expansion raised the market price to 1oz = £7, it would make sense to take a £5 note to the bank, swap it for an ounce of gold and sell it on the market for £7.

The same process worked in reverse against monetary contractions. A fall in the market price to 1oz = £3 would make it profitable to buy an ounce of gold, take it to the bank and swap it for £5.

In both cases the convertibility of currency into gold and vice versa would act against the monetary expansion or contraction. In the case of an expansion gold would flow out of banks forcing a contraction in the currency if banks wished to maintain their reserve ratios. Likewise a contraction would see gold flow into banks which, again, in an effort to maintain their reserve ratios, would expand their issue of currency.

The gold standard era was one of incredible monetary stability; the young John Maynard Keynes could have discussed the cost of living with Samuel Pepys without adjusting for inflation. The minimisation of inflation risk and ease of convertibility saw a massive growth in trade and long term cross border capital flows. The gold standard was a key component of the period known as the ‘First era of globalisation’.

The judgement of economic historians Kenwood and Lougheed on the gold standard was

One cannot help being impressed by the relatively smooth functioning of the nineteenth-century gold standard, more especially when we contemplate the difficulties experienced in the international monetary sphere during the present century. Despite the relatively rudimentary state of economic knowledge concerning internal and external balance and the relative ineffectiveness of government fiscal policy as a weapon for maintaining such a balance, the external adjustment mechanism of the gold standard worked with a higher degree of efficiency than that of any subsequent international monetary system

The gold exchange standard and devaluation

The First World War shattered this system. Countries printed money to fund their war efforts and convertibility and exportability were suspended. The result was a massive rise in prices.

After the war all countries wished to return to the gold standard but were faced with a problem; with an increased amount of money circulating relative to a country’s gold stock (a problem compounded in Europe by flows of gold to the United States during the war) the parity prices of gold were far below the market prices. As seen earlier, this would lead to massive outflows of gold once convertibility was re-established.

There were three paths out of this situation. The first was to shrink the amount of currency relative to gold. This option, revaluation, was that taken by Britain in 1925 when it went back onto the gold standard at the pre-war parity.

The second was that largely taken by France between 1926 and 1928. This was to accept the wartime inflation and set the new parity price at the market price.

There was also a third option. The gold stock could not be expanded beyond the rate of new discoveries. Indeed, the monetary stability which was a central part of the gold standard’s appeal rested on the fixed or slow growth of the gold stock which acted to halt or slow growth in the currency it backed. So many countries sought to do the next best thing and expand gold substitutes to alleviate a perceived shortage of gold. This gave rise to the gold exchange standard which was put forward at the League of Nations conference in Genoa in 1922.

Under this system countries would be allowed to add to their gold reserves the assets of countries whose currency was convertible into gold and issue domestic currency based on this expanded stock. In practice the convertible currencies which ‘gold short’ countries sought as reserves were sterling and dollars.

The drawbacks were obvious. The same unit of gold could now have competing claims against it. The French took repeated advantage of this to withdraw gold from Britain.

Also it depended on the Bank of England and Federal Reserve maintaining the value of sterling and the dollar. There was much doubt that Britain could maintain the high value of sterling given the dire state of its economy and the dollar was weakened when, in 1927, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates in order to help ease pressure on a beleaguered sterling.

This gold exchange standard was also known as a ‘managed’ gold standard which, as Richard Timberlake pointed out, is an oxymoron. “The operational gold standard ended forever at the time the United States became a belligerent in World War I”, Timberlake writes.

After 1917, the movements of gold into and out of the United States no longer even approximately determined the economy’s stock of common money.

The contention that Federal Reserve policymakers were “managing” the gold standard is an oxymoron — a contradiction in terms. A “gold standard” that is being “managed” is not a gold standard. It is a standard of whoever is doing the managing. Whether gold was managed or not, the Federal Reserve Act gave the Fed Board complete statutory power to abrogate all the reserve requirement restrictions on gold that the Act specified for Federal Reserve Banks (Board of Governors 1961). If the Board had used these clearly stated powers anytime after 1929, the Fed Banks could have stopped the Contraction in its tracks, even if doing so exhausted their gold reserves entirely.

This was exacerbated in the United States by the Federal Reserve adopting the ‘real bills doctrine’ which held that credit could be created which would not be inflationary as long as it was lent against productive ‘real’ bills.

Many economists, notably Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek, have seen the genesis of the Depression of the 1930s in the monetary architecture of the 1920s. While this remains the most debated topic in economic history there is no doubt that the Wall Street crash and its aftermath spelled the end of the gold exchange standard. When Britain was finally forced to give up its attempt to hold up sterling and devalue in 1931 other countries became worried that its devaluation, by making British exports cheaper, would give it a competitive advantage. A round of ‘beggar thy neighbour’ devaluations began. Thirty two countries had gone off gold by the end of 1932 and the practice continued through the 1930s.

Bretton Woods and its breakdown

Towards the end of World War Two economists and policymakers gathered at Bretton Woods in New Hampshire to design a framework for the post war economy. Looking back it was recognised that the competitive devaluations of the 1930s had been a driver of the shrinkage of international trade and, via its contribution to economic instability, to deadly political extremism.

Thus, the construction of a stable monetary framework was of the most utmost importance. The solution arrived at was to fix the dollar at a parity of 1oz = $35 and to fix the value of other currencies to the dollar. Under this Bretton Woods system currencies would be pegged to gold via the dollar.

For countries such as Britain this presented a problem. Any attempt to use expansionary fiscal or monetary policy to stimulate the economy as the then dominant Keynesian paradigm prescribed would eventually cause a balance of payments crisis and put downward pressure on the currency, jeopardising the dollar value of sterling. This led to so called ‘stop go’ policies in Britain where successive governments would seek to expand the economy, run into balance of payments troubles, and be forced to deflate. In extreme circumstances sterling would have to be devalued as it was in 1949 from £1 = $4.03 to £1 = $2.80 and 1967 from £1 = $2.80 to £1 = $2.40.

A similar problem eventually faced the United States. With the dollar having replaced sterling as the global reserve currency, the United States was able to issue large amounts of debt. Initially the Federal Reserve and Treasury behaved reasonably responsibly but in the mid-1960s President Lyndon Johnson decided to spend heavily on both the war in Vietnam and his Great Society welfare program. His successor, Richard Nixon, continued these policies.

As dollars poured out of the United States, investors began to lose confidence in the ability of the Federal Reserve to meet gold dollar claims. The dollar parity came under increasing pressure during the late 1960s as holders of dollar assets, notably France, sought to swap them for gold at the parity price of 1oz = $35 before what looked like an increasingly inevitable devaluation. Unwilling to consider the deflationary measures required to stabilise the dollar with an election due the following year, President Nixon closed the gold window on August 15th 1971. The Bretton Woods system was dead and so was the link between paper and gold.

Fiat money and floating exchange rates

There were attempts to restore some semblance of monetary order. In December 1971 the G10 struck the Smithsonian Agreement which sought to fix the dollar at 1oz = $38 but this broke down within a few months under the inflationary tendencies of the Federal Reserve. European countries tried to establish the ‘snake’, a band within which currencies could fluctuate. Sterling soon crashed out of even this under its own inflationary tendencies.

The cutting of any link to gold ushered in the era of fiat currency and floating exchange rates which lasts to the present day. Fiat currency gets its name because its value is given by governmental fiat, or command. The currency is not backed by anything of value but by a politicians promise.

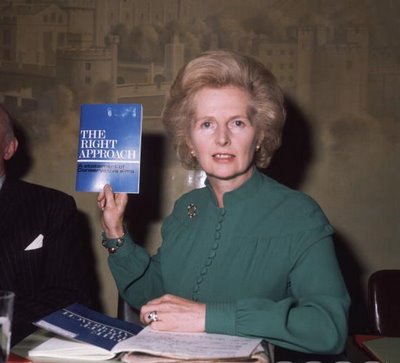

The effect of this was quickly seen. In 1931 Keynes had written that “A preference for a gold currency is no longer more than a relic of a time when governments were less trustworthy in these matters than they are now” But, as D R Myddelton writes, “The pound’s purchasing power halved between 1945 and 1965; it halved again between 1965 and 1975; and it halved again between 1975 and 1980. Thus the historical ‘half-life’ of the pound was twenty years in 1965, ten years in 1975 and a mere five years in 1980”

In 1976 the pound fell below $2 for the first time ever. Pepys and Keynes would now have been talking at cross purposes.

Floating exchange rates marked the first public policy triumph for Milton Friedman who as long ago as 1950 had written ‘The Case for Flexible Exchange Rates’. Friedman had argued that “A flexible exchange rate need not be an unstable exchange rate” but in an era before Public Choice economics he had reckoned without the tendency of governments and central banks, absent the restraining hand of gold, to print money to finance their spending. World inflation which was 5.9% in 1971 rose to 9.6% in 1973 and over 15% in 1974.

The experience of the era of floating exchange rates has been of one currency crisis after another punctuated by various attempts at stabilisation. The attempts can involve ad hoc international cooperation such as the Plaza Accord of 1985 which sought to depreciate the dollar. This was followed by the Louvre Accord of 1987 which sought to stop the dollar depreciating any further.

They may take more organised forms. The Exchange Rate Mechanism was an attempt to peg European currencies to the relatively reliable Deutsche Mark. Britain joined in 1990 at what many thought was too high a value (shades of 1925) and when the Bundesbank raised interest rates to tackle inflation in Germany sterling crashed out of the ERM in 1992 but not before spending £3.3 billion and deepening a recession with interest rates raised to 12% in its vain effort to remain in.

Where now?

This brief look back over the monetary arrangements of the last hundred years shows that currency issuers, almost always governments, have repeatedly pushed the search for seigniorage to the maximum possible within the given monetary framework and have then demolished this framework to allow for a more ‘elastic’ currency.

Since the demise of the ERM the new vogue in monetary policy has been the independent central bank following some monetary rule, such as the Bank of England and its inflation target. Inspired by the old Bundesbank this is an attempt to take the power of money creation away from the politicians who, despite Keynes’ high hopes, have proved themselves dismally untrustworthy with it. Instead that power now lies with central bankers.

But it is not clear that handing the power of money creation from one part of government to another has been much of an improvement. For one thing we cannot say that our central bankers are truly independent. The Chairman of the Federal Reserve is nominated by the President. And when the Bank of England wavered over slashing interest rates in the wake of the credit crunch, the British government noisily questioned its continued independence and the interest rate cuts came.

Furthermore, money creation can reach dangerous levels if the central bank’s chosen monetary rule is faulty. The Federal Reserve has the awkward dual mandate of promoting employment and keeping prices stable. The Bank of England and the European Central Bank both have a mandate for price stability, but this is problematic. As Murray Rothbard and George Selgin have noted, in an economy with rising productivity, prices should be falling. Also, what ‘price level’ is there to stabilise? The economy contains countless different prices which are changing all the time; the ‘price level’ is just some arbitrarily selected bundle of these.

An extreme example, as noted by Jesús Huerta de Soto, is the euro. Here a number of governments agreed to pool their powers of money creation and invest it in the European Central Bank. The euro is now widely seen to be collapsing. So it may be, but is this, as is generally assumed, a failure of the architecture of the euro itself?

Let us remember that the purpose of erecting a monetary structure where the power to create money is removed from government is to stop the government running the printing presses to cover its spending and, in so doing, destroy the currency.

The problem facing eurozone states like Greece and Spain is presented as being that they are running up debts in a currency they cannot print at will to repay these debts. But is the problem here that these countries cannot print the money they need to pay their debts or that they are running up these debts in the first place? The solution is often offered that either these countries need to leave the euro and adopt a currency which they can expand sufficiently to pay their debts or that the ECB needs to expand the euro sufficiently for these countries to be able to pay their debts. But there is another solution, commonly called ‘austerity’, which says that these countries should just not run up these debts. As de Soto argues, the euro’s woes are really failures of fiscal policy rather than monetary policy.

It is thus possible to argue that the euro is working. By halting the expansion of currency to pay off debts and protecting its value and, by extension, preventing members from running up evermore debt, the euro is doing exactly what it was designed to do.

There is a growing clamour inside Europe and outside that ‘austerity’ alone is not the answer to the euro’s problems and that monetary policy has a role to play. The ECB itself seems to be keen to take on this role. But it is simply the age-old idea, based on the confusion between the real and the nominal, that we will get richer if we just produce more money. Germany is holding the line on the euro but history shows that far sounder currency arrangements have collapsed under the insatiable desire for a more elastic currency.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, B.M. 1949. Economics and the Public Welfare – A Financial and Economic History of the United States 1914-1946. North Shadeland, Indiana: Liberty Press

BAGUS, P. 2010. The Tragedy of the Euro. Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

CAPIE, F., WOOD, G. 1994. “Money in the Economy 1870-1939.” The Economic History of Britain since 1700 vol. 2: 1860-1939. Roderick Floud and D.N. McCloskey, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 217-246.

DRUMMOND, I. 1987. The Gold Standard and the International Monetary System 1900-1939. London: Macmillan

FRIEDMAN, M. 1950. “The Case for Flexible Exchange Rates” Essays in Positive Economics. 1953. Friedman, M. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 157-203.

HOWSON, S. 1994. “Money and Monetary Policy in Britain 1945-1990.” The Economic History of Britain since 1700 vol. 3: 1939-1992. Roderick Floud and D.N. McCloskey, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 221-254.

HUERTA DE SOTO, J. 2012. “In defence of the euro: an Austrian perspective”. The Cobden Centre, May 29th

KENWOOD, A.G., LOUGHEED, A.L. 1992. The Growth of the International Economy 1820-1990. London and New York: Routledge

KINDLEBERGER, C.P. The World in Depression 1929-1939. London: Pelican

MYDDELTON, D.R. 2007. They Meant Well – Government Project Disasters. London: Institute of Economic Affairs

ROTHBARD, M. 1963. America’s Great Depression. BN Publishing

SAMUELSON, R.J. 2010. The Great Inflation and its Aftermath – The Past and Future of American Affluence. New York: Random House

SELGIN, G. 1997. Less Than Zero – The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy. London: Institute of Economic Affairs

TIMBERLAKE, R. 2008. “The Federal Reserve’s Role in the Great Contraction and the Subprime Crisis”. Cato Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2008), James A. Dorn, ed. Washington DC: Cato Institute, pp. 303-312.

VAN DER WEE, H. 1986. Prosperity and Upheaval – The World Economy 1945-1980. London: Pelican

This article originally appeared at The Cobden Centre